What Next for Climate Risk?

11 May 2022

Climate risk is high on the agenda of many banks and creating a hive of activity behind the scenes. For those that took part in the PRA Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) exercise and for those in Europe who are going through the ECB Climate Risk Stress Test (CST), estimating how portfolios will be impacted from Physical and Transition Risks with associated financial impacts certainly is a new challenge to overcome, but what changes will this drive?

The first area of focus will most certainly be enhancing disclosures.

“All in all, none of the 115 banks directly supervised by the ECB fully meets our supervisory expectations for disclosures.” Mr Frank Elderson, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank and Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB

The ECB’s 2021 stocktake of banks climate-related and environmental risk disclosures found that Supervised banks are not meeting expectations for disclosures. Within his keynote speech, Mr Frank Elderson, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank and Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, also suggested that there was a lot of white noise in disclosure to compensate for poor quality. This highlights the critical need for banks to focus on the transparency of their disclosures in order to provide clarity on how they are exposed to Climate & Environmental risks and how they are managing those risks.

Incorporating climate risk into the capital regime

Another area of concern for banks is how climate risk will be incorporated into the capital regime in a similar way to other risks such as Credit, Market and Operational Risk. Whilst regulators will decide on the best mechanism to protect the banking system from climate related financial risks, it is important to consider what unintended consequences may be detrimental to fighting climate change. For example, if penal capital charges are applied when lending to industries or business that currently have high emissions, it will increase the borrowing costs and cut off funding required for those businesses to greenify their operations in order to meet their Net-Zero Carbon targets. At a broader level there is a debate around the potential and desirability of using regulatory capital requirements to steer bank funding to drive investment to support greening the economy and not just to provide a prudential cushion. This would require regulators to be given a new legal remit and is likely politically contentious.

Inclusion within Risk Appetite and Credit Assessment

The move to a greener economy will include lending to some business who don’t yet have an environmentally sustainable operation but require funding to move to a cleaner model and it is important that the right guardrails are in place to manage this responsibly within an organisation.

Firstly, the assessment and reporting of the physical and transition risks needs to feed into the banks risk appetite and secondly, the strategy to achieve environmental sustainability of the businesses beyond the scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions need to form part of the credit assessment process.

A great example of this is a model created by 4most which combined quantitative and qualitative factors from TCFD disclosures to create a climate rating. The qualitative factors summarise the green credentials of the organisation and could help to ensure that those organisations that are serious in their green ambitions are not priced out of the credit needed to achieve their goals. Also, whilst the model was developed using TCFD disclosures from FTSE companies, the criteria used to create the quantitative factors can be used as a Climate Transition Risk questionnaire that relationship managers could use for smaller commercial entities as part of the rating process.

Impact on Consumer Finance and Lending

Banks also need to think about how climate risks will affect consumer finance. As more granular and sophisticated climate risk models are developed, their use within credit decisions needs to evolve. We are already seeing some banks offer preferential mortgage products for more energy efficient properties, but that is just the start. For example, should maximum loan amounts and affordability assessments be tiered based on the EPC rating of a property due to the costs of making the required improvements? With future capital and impairment charges linked to Physical and Transition risks, will banks subsidise home improvement loans or EPC re-ratings that will improve their capital position and will physical risks, such as flooding, be assessed and used to set maximum Loan to Value amounts?

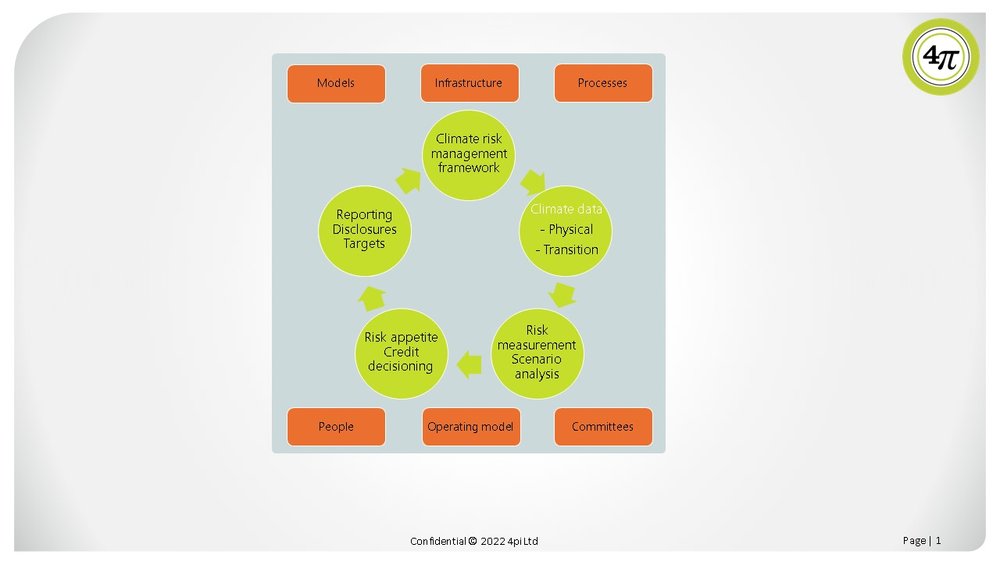

Embedding climate risk within Internal Control Frameworks

All of the considerations above need to be incorporated into a banks operating model, with the ECB recently announcing their support for the proposals by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union that will help to ensure that institutions proactively develop enhanced risk management frameworks to tackle environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks, whilst the PRA asking the largest firms to prepare a report on how they have embedded the management of climate-related financial risks into their existing risk management frameworks.

The need for a Climate Risk Framework that provides a consistent approach to climate change risk management across origination, portfolio management and reporting, whilst embedding the new climate change requirements into existing governance structures and processes is clear. With all of these considerations it is not a far stretch to imagine the adoption of a climate risk use-test that will help banks confirm to regulators and consumers that their consideration of climate change is not just white noise.

If you have any questions or want to discuss how we can support your challenges to climate related risks,

please contact info@4-most.co.uk

Interested in learning more?

Contact usInsights

UK Deposit Takers Supervision – 2026 Priorities: What banks and building societies need to know about the PRA’s latest Dear CEO letter

21 Jan 26 | Banking

EBA publish final ‘Guidelines on Environmental Scenario Analysis’: What European banks need to know about the future of managing ESG risks

19 Dec 25 | Banking

Solvency II Level 2 Review finalised: What insurers should focus on before 2027

17 Dec 25 | Insurance