The European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines published in 2017 (EBA/GL/2017/16) provided guidance on the approach for dealing with cures within Loss Given Default (LGD) developments:

“135 In the case of exposures that return to non-defaulted status, institutions should calculate economic loss as for all other defaulted exposures with the only difference that an additional recovery cash flow should be added to the calculation as if a payment had been made by the obligor in the amount that was outstanding at the date of the return to non-defaulted status, including any principal, interests and fees (‘artificial cash flow’).”

This approach is common in unsecured LGD modelling where explicit cashflow modelling is undertaken and the cure is therefore treated as an additional cashflow, rather than a separate component of the model (although other approaches do exist).

Unlike direct cashflow modelling, the standard approach for secured portfolios breaks the calculation into separate components, including a probability of possession given default (unsecured approaches can use a probability of write-off which can bring the same issues under the new regulation). This component is then used to factor the loss in the event of possession by the probability of the possession occurring. This approach has an implicit assumption that cures (probability of possession not occurring) have a zero loss.

For mortgages, the zero-loss assumption for cures has always been seen as reasonable since interest is generally accrued to the balance during the default period and costs are low as a proportion of the balance, resulting in an immaterial economic loss.

However, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) Consultation Paper on the Guidelines (CP 21/19), confirms that this approach is no longer considered appropriate:

“2.24 The PRA considers it necessary to clarify the approach required by the GL on PD & LGD25 to discounting cured exposures in order to avoid inconsistent interpretations of the guidelines. The PRA considers that the proposed approach most accurately reflects the economic reality of the exposures and timing of the cash flows. The PRA also considers the common UK industry practice of assuming zero loss for cures to be insufficiently prudent and therefore considers this expectation will result in a proportionate but more conservative treatment of cured exposures”

For mortgages, the likely result could be a material derived loss in the event of cure due to the mismatch between the account interest rate and the 9% discount floor required for downturn LGD estimates. This mismatch results in the vast majority of mortgage products registering a discounted loss even if interest is accrued as expected during the period in default.

As this loss is agnostic to the severity of the default event (performing accounts would also register a loss on a 9% discounted cashflow basis) this could lead to potential reconsideration of definitions of default, and in particular those with high cure rates and a long lead time to genuinely cure (it should be noted that any probation or independence period is excluded from the calculation). Examples of default events that could become overly punitive are bankrupts with no deterioration on the mortgage product, cross product defaults and payment holidays where the customer is unable to catch up with missed payments. Additionally, with regards to this last point, consideration should be given to collections practices including the speed of rehabilitation and toolsets available such as the capitalisation of arrears.

However, the priority should undoubtedly be compliance, and therefore consideration needs to be given to address this requirement in the LGD models to meet likely future regulation (this is currently a Consultation Paper, but all indications from the PRA is that it is unlikely to change in the final Policy).

Whilst there is an option to develop direct cashflow models to predict the whole LGD (similar to unsecured), it is more likely that firms will opt to incorporate a separate component into existing LGD structures and mirror that used in Loss Given Repossession (LGR) approaches. Whereby, a Loss Given Cure (LGC) will be calculated which is then multiplied by the probability of curing (1-PPD) to arrive at an amount to add to the current LGD (excluding the LGC).

With this in mind, two main approaches can be considered to estimate the LGC:

1. Direct modelling of LGC to be applied on an overall/segment level

2. A component-based approach utilising account specific rates.

The first option is to directly model LGC based on observed historic data. This approach would be deployed by assigning each account a direct LGC based on any segmentation applied within the development. The development would be conducted by modelling the Net Present Value (NPV) of the ‘real cashflows’ and the ‘artificial cashflows’ for accounts that cure. The resulting dataset can then be used to produce an overall average LGC or segmentation could be considered.

The second option is to break the calculation into key components and calculate the LGC for each account dynamically in the live monthly model. The structure of the model would be similar to that used in LGR, whereby the balance at the point of cure would be estimated in addition to the average time to cure.

The two approaches offer both advantages and disadvantages with regard to accuracy of the estimates and subsequent maintenance.

Investigative work has been undertaken within 4most to understand the materiality of these choices on the final approach. The main considerations have been the impact of interim payments not accounted for in the basic component approach, the potential distribution of the time to cure not accounted for in the basic component approach and the future account level variation in interest rates not accounted for in the direct modelling approach.

Whilst the impact will vary by organisation, the largest potential impact appears to be the consideration of differing interest rates.

The impact of account specific interest rates will affect the accuracy of the model both in terms of granularity (account level accuracy) and over time as portfolio rates change. For example, from our analysis, a 1% variation in absolute customer rates can result in an LGC variation of over 25%. This can bring material movements between accounts, but more importantly, as any future material movements in rates can only realistically be an increase, this could lead to significant conservatism in future estimates.

The impact of this regulatory change on models, risk practices and levels of risk weights is yet to be fully understood, but it appears to have more material implications than some organisation are considering at the moment.

To support this understanding, 4most have undertaken some indicative impact assessments using our knowledge of LGD parameters used within the industry and potential Loss Given Cure average values.

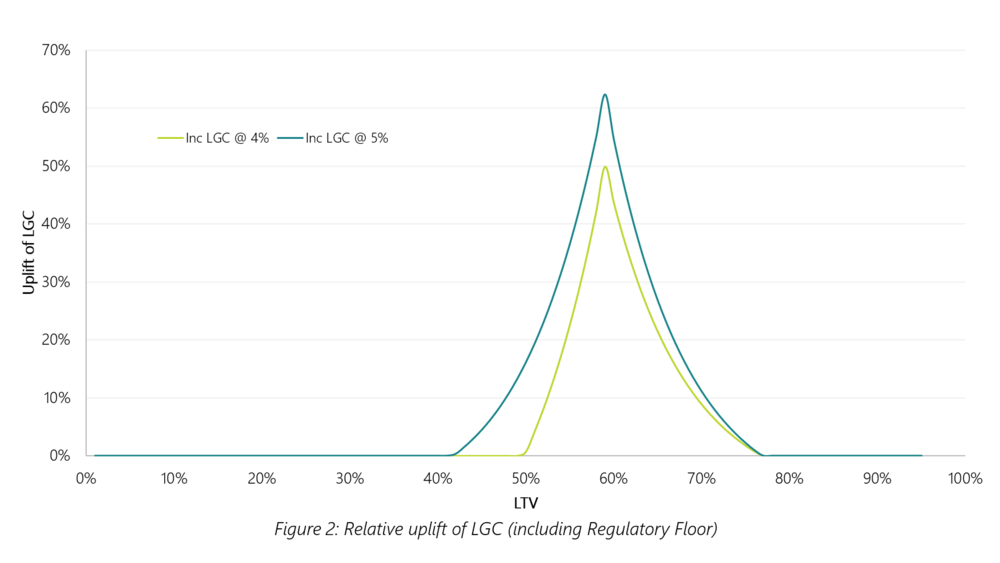

When the relative movements and regulatory floors are considered it can be clearly seen that the mid-range LTVs will be hardest hit. The below chart shows the relative increase in DT LGD if Loss Given Cure was to be set at a flat 4% or 5%.

The increases seen for circa 60% LTVs of 50% – 60% (dependent upon LGC value) will likely worry a number of lenders who target this range as low risk new customers in attempts to provide efficient portfolio growth.

Given the analysis required to understand the organisation specific impacts of model changes on business plans and the lead-time to collect data on the impacts of risk changes on model estimates, it is clear why we are starting to see some more eager firms trying to get ahead of the curve.

For more information or to see how we can help your business, get in touch with Chris at christopher.warhurst@4-most.co.uk.